As the Farm Bill of 2018, which legalized hemp federally in the U.S., comes up for renewal this year, many in the hemp and cannabis industries are hoping for clarity on fundamental questions of what qualifies as industrial hemp, how CBD should be regulated, and where hemp-derived THC products fit into the federal regulatory regime.

Whether they will get it — or be satisfied by the results — in a massive omnibus appropriations bill, remains to be seen.

“Given the complexity of the Farm Bill and the focus on the agricultural side of things rather than FDA jurisdiction, we would most likely see the Farm Bill to address the current definition of hemp while Congressional committees that oversee the FDA and other committees work on a regulatory pathway for such products,” said Erin Moffet, spokeswoman for the Cannabis Financial Industry Group.

The current Farm Bill, technically the “Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018”, expires in September. Jonathan Miller, general counsel for the U.S. Hemp Roundtable, told CRB Monitor he heard that Rep. Glenn Thompson, chair of the House Committee on Agriculture, will be drafting a bill in the next few weeks and hopes to pass it through the House by end of September. But Miller added that may be optimistic, and it could be next year before a new Farm Act reaches the president’s desk.

Emails and a phone call to Thompson’s spokeswoman seeking comment were unreturned.

Hemp: CBD vs. THC

When hemp was legalized five years ago, most people thought of fiber, edible seed and oil as the most common products from a renewed crop that would boost the ag industry. But a sub-industry of novel cannabinoid producers has emerged, using legal hemp with its nominal THC content to create products such as cosmetics, tinctures and edibles. These hemp-derived consumables are sold at major retail outlets, convenience stores and gas stations nationwide, in most cases without any legal or regulatory restrictions as to recommended use, purity, safety or labeling. Many of these products are sold as THC-like products online and in states where high-THC cannabis is still illegal or highly restricted.

The U.S. cannabinoid market was valued at $13.8 billion in 2022, according to a June research report by Skyquest. Meanwhile, industrial hemp production and value has been dramatically shrinking, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The legal context for novel cannabinoid products lies in the regulation of cannabidiol (CBD), the non-intoxicating compound that naturally occurs in the hemp plant and is believed to have therapeutic benefits, as well as naturally occurring delta-8 and delta-9 THC, each of which can be refined and synthesized into hemp-derived but intoxicating high-THC products. THC can be made through natural or synthetic conversion of legal CBD to delta-8 THC and other derivatives. The Drug Enforcement Agency has stated that naturally occurring CBD and THC derived from hemp are not controlled substances, but the agency recently declared synthetic THC acetates (commonly known as “THC-O”) Schedule 1 drugs under the CSA, the same designation as delta-9 THC, and is reportedly creating rules for other synthetic cannabinoids.

CBD regulation currently falls under the Food and Drug Administration, which says CBD cannot legally be sold as a dietary supplement or as a food ingredient under the Federal Food Drug & Cosmetic Act.

Because the FDA has already evaluated CBD as a drug for Epidiolex and was subject to clinical studies, it says it cannot regulate CBD as a food additive or supplement without going through the traditional rulemaking process. In January, it rejected three citizen petitions to issue regulations to market CBD as dietary supplements.

“Such a regulation would be needed in order to provide a potential pathway for CBD products to be lawfully marketed as dietary supplements, because a provision in the law prohibits the marketing of certain drug ingredients as dietary supplements, the FDA said in the Jan. 26 constituent update. “The FDA’s responses explain that we do not intend to initiate such a rulemaking, because in light of the available scientific evidence, it is not apparent how CBD products could meet the applicable safety standard for dietary supplements.”

In a separate FDA statement, Dr. Janet Woodcock, principal deputy commissioner, explained the safety concerns, especially for long-term use. “Studies have shown the potential for harm to the liver, interactions with certain medications and possible harm to the male reproductive system. CBD exposure is also concerning when it comes to certain vulnerable populations such as children and those who are pregnant,” she said.

The agency, therefore, has appealed to Congress to help create a “new regulatory pathway” to regulate and enforce the safety of these products.

“The FDA recently concluded that a new regulatory pathway for hemp derived products is needed because of the potential risk of CBD to human and animal health, as the existing foods and dietary supplement authorities provide only limited tools to manage the risks associated with CBD,” said an FDA spokeswoman in an email to CRB Monitor. “The agency is prepared to work with Congress on a new regulatory pathway that could provide safeguards and oversight to manage these risks.”

Still, the House Committee on Appropriations said, in a report for a USDA and FDA appropriations bill this month, that the FDA already has plenty of existing tools to set guidance and go after bad actors in the CBD market, and they expect the agency to do so.

“The Committee recognizes FDA’s use of existing authorities to undertake cannabis-related efforts, including research, requests for data, consumer education, issuance of guidance and policy around cannabis-based drug product development, and enforcement against wrongdoers. The Committee expects FDA to continue and increase these efforts given the proliferation of non-FFDCA-compliant, cannabis-containing products and the risks they pose to public health,” particularly enforcement of “products marketed with unlawful therapeutic claims,” the report said.

Stakeholders dig their trenches for hemp regulation

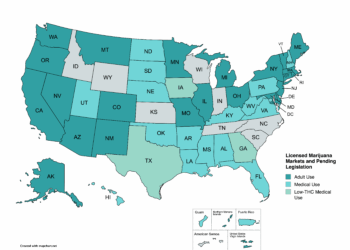

The lack of federal oversight of novel cannabinoids has led a growing number of states to set their own patchwork of laws, ranging from full-scale bans of hemp-derived products to more general definitions and regulations. This has pitted traditional industrial hemp farmers against legal cannabis manufacturers and CBD retailers against legal cannabis retailers.

On May 9, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed SB 5367 into law. The legislation requires CBD products to have 0% THC. Otherwise, sales would require licensure by the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) by July 23. The board is scheduled to initiate the rulemaking process on July 21.

Harris Bricken attorney Jack Scranton noted in the law firm’s blog that via the 2018 Farm Act, regulators have determined products containing 0.3% delta-9 THC are non-intoxicating.

“So, the insistence by Washington lawmakers that hemp-derived CBD products contain 0.0% of any THC isomer doesn’t read like a public health initiative,” Scranton wrote. “Rather, it seems like the cannabis lobby successfully using the lawmaking process to recapture a significant part of the CBD industry.”

The problem, state regulators assert, is that finished hemp products can have THC levels far above the 0.3% THC limit. The Cannabis Regulators Association calls it the ”0.3% loophole” in an April 17 letter to Congress “urging” for clearer hemp-derived cannabinoid policy.

CANNRA represents cannabis and hemp regulatory agencies from more than 40 states and U.S. territories. Executive Director Gillian Schauer told CRB Monitor that exact policy positions vary from member to member, but hemp-derived cannabinoids are an issue for every state regulator. She said protecting customer safety is hard to do when they don’t have the authority to do so.

“Every [member] regulator would like to see federal regulators get engaged,” in setting minimum safety standards, Schauer said.

CANNRA, in its letter, identified 10 key considerations toward a stronger regulatory framework. They start with clarifying the definition of hemp in the Farm Bill to state that the 0.3% threshold only applies to plants, not finished products. Schauer said many regulators would like to see a separation of agriculture from cannabinoid products. One approach could be to define industrial hemp in the Farm Bill and leave its oversight with the Department of Agriculture, cleaving off non-industrial hemp products for regulation by the FDA.

She said there needs to be a limit to the amount of finished THC in legal hemp products, but there’s a lot of debate on where to set the line.

CANNRA also recommends engaging all the federal agencies that should have regulatory oversight over hemp products, not only the FDA and Department of Agriculture, but the Environmental Protection Agency for pesticide control and the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax & Trade Bureau (TTB) for taxing mechanisms.

If legislation directs certain agencies with oversight and rulemaking, they definitely need a timeline, she said. “State regulators have been dealing with this problem for three years at least; we don’t have another 10 years.”

She said she can’t see a regulatory framework without the FDA setting safety standards for a wide range of things, from additives to testing to package labeling. “I personally would like to see the FDA act, and act fast,” Schauer said. But she understands the agency is in a difficult position because hemp products can be consumed in so many ways.

“One challenge is this industry has been extremely innovative,” she said.

Schauer said CANNRA isn’t a lobbying organization, but “regulators have a unique perspective and should have a seat around the table.”

Disagreement remains on the path forward

Miller said the Hemp Roundtable wants to see regulation but opposes criminalization of hemp derivatives for adult use. He said the organization would like to see federal legislation modeled after laws recently passed in Kentucky, Tennessee and Florida.

Miller said that hopefully the Farm Bill will regulate CBD and non-intoxicating products. They want to see the TTB regulate adult-use, hemp-derived THC while the FDA maintains jurisdiction over non-intoxicating CBD.

Nonetheless, significant differences remain among industry and regulatory groups seeking better regulation of novel cannabinoids. The Hemp Roundtable took issue with a recent FDA article regarding the oral toxicity of CBD. In a May 30 letter to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Miller wrote that the article “fails to provide a full picture of the available data on CBD, and instead focuses primarily on studies using high-dose CBD formulations – ignoring the growing body of evidence demonstrating the safety of CBD at lower amounts.”

He also said that “CBD is being held to a much higher standard than other dietary supplement ingredients.”

When it comes to legislation already introduced in Congress to ring-fence hemp derivatives, the Hemp Roundtable supports HR 1629, which would allow hemp, CBD derived from hemp, and other hemp-derived products to be used as a dietary supplement, as well as HR 1628, which directs the FDA to regulate CBD as a food ingredient.

There’s some opposition, however, to the Industrial Hemp Act (S 980/HR 3755), which he said would allow a “complete exemption on hemp” producers.

But he doesn’t expect these bills to pass on their own. They more likely would be wrapped into the Farm Bill. “We’ll be working behind the scenes on these bills, either as stand-alone or in the Farm Bill,” Miller said.