As Congress punts the renewal of the U.S. Farm Act another year, dueling federal court opinions on whether states can regulate hemp-derived cannabinoids head to separate appellate courts.

If the circuit courts concur with their lower court rulings resulting in a circuit court split, and Congress doesn’t act in the meantime, the issue could very well end up before the U.S. Supreme Court, attorneys fighting these cases said.

In Virginia, U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema detailed her reasoning that the state does have the right to limit the “total THC” in consumable products.

“The only activity the Farm Act expressly preempts is any state-imposed restrictions on the interstate transportation and shipment of industrial hemp through the Commonwealth. Other than that limitation, the Farm Act expressly permits states to retain ‘primary regulatory authority over the production of hemp,’” Brinkema wrote in a Oct. 30 memorandum opinion that denied an injunction to implement Virginia’s new law.

The plaintiffs — a Virginia-based hemp products retailer, a North Carolina-based hemp products producer and a Virginia woman who uses hemp-derived THC products – appealed the ruling to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals on Nov. 9.

Meanwhile, in Arkansas, U.S. District Court Judge Billy Roy Wilson came to the opposite opinion and granted a preliminary injunction on the state’s ban on “synthetic” hemp-derived THC substances, including delta-8, delta-10 and delta-10 THC.

“Defendants contend that the products at issue here are Schedule I substances because they are ‘synthetic.’ However, the 2018 Farm Bill’s definition of hemp does not limit its application to [the] method ‘derivatives, extracts, [and] cannabinoids’ are produced. Instead, the definition covers all downstream products if they do not cross the 0.3 percent delta-9 THC threshold,” Wilson wrote in his Sept. 7 order.

Arkansas appealed the order to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals on Oct. 6.

Legal chaos as hemp industry challenges state laws

The confusion and sense of urgency stems from the 2018 Farm Act’s definition of legal industrial hemp “as any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

What lawmakers didn’t know then was that psychoactive derivates containing high concentrations of THC — such as delta-8, delta-10 and others — could be created and infused into all types of products, including food, oils and inhaled vapes. These products coming from legal hemp have been sold nationwide, even in states where marijuana is illegal, without regulatory oversight and are easily purchased and consumed by children. In states where marijuana is legal, these products compete with licensed businesses.

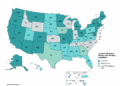

With unclear federal regulation and lax enforcement, states have picked up the mantle and began creating laws to regulate hemp-derived cannabinoids. But manufacturers and retailers, (and in Virginia’s case, a consumer) are fighting back.

In recent months, legal challenges to state hemp laws have emerged in New York, Alaska, Florida, Georgia and Maryland state courts.

These fights have also been fought in federal courts in Hawaii and Indiana, both of which ruled for state rights.

In 2020, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed a district court’s broad injunction on a 2019 Indiana law that prohibited the manufacture, delivery or possession of smokable hemp products, which Brinkema cited in her ruling.

“The Farm Act ‘authorizes the states to continue to regulate the production of hemp, and its express preemption clause places no limitations on a state’s right to prohibit the cultivation or production of industrial hemp or derivative products,’” she wrote, citing the Seventh Circuit’s ruling in C.Y. Wholesale Inc., et al. v. Eric Holcomb, et. al.

The hair-splitting issue in these cases is the Farm Act’s use of the word “production.” Does it strictly mean cultivating the plant? Or does it include the manufacturing of hemp products, thereby allowing states to regulate businesses or even ban certain products? Attorneys, and the deciding judges, have defined the word differently.

In the C.Y. Wholesale case, “Plaintiffs argued that ‘production’ refers only to the growing of crops, while ‘manufacture’ refers to the act of converting raw hemp into another form, i.e., a smokable product,” Brinkema stated in a footnote. “Plaintiffs here make similar arguments, attempting to constrain the reading of “production” in the Farm Act to not include the creation of hemp products that contain delta-8 THC. The Seventh Circuit did not accept that argument, nor will this Court.”

“That’s not what production means,” said James Markels, a partner at the Virginia law firm Croessman & Westberg, representing the plaintiffs. “The Farm Act is pretty clear, production means cultivation.”

A spokeswoman for the Virginia Attorney General’s office said in an email, “We do not comment on pending litigation.” A call to the Arkansas Attorney General’s office was not returned.

Courts find delta-8 THC is legal

Meanwhile, other legal challenges have questioned whether THC derivatives other than delta-9 are legal hemp products. Last year, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled as part of a trademark infringement case in California that delta-8 THC “appears to fit comfortably within the statutory definition of ‘hemp.’”

In the case of AK Futures LLC v. Boyd Street Distro LLC, the Ninth Circuit panel wrote, “Any congressional intent that the Farm Act legalize only industrial hemp, not a potentially psychoactive substance like delta-8 THC, appears neither in hemp’s definition nor in its exemption from the Controlled Substances Act.”

Since delta-8 THC was federally legal, the court ruled that AK Futures was “likely to succeed” in its claim that Body Street violated its copyright and trademark for a vape product.

In Georgia, authorities seized thousands of products containing delta-8 and delta-9 THC, as well as currency, from Elements Distribution in February. After a legal challenge, the Gwinett County district attorney acknowledged that non-edible delta-8 and delta-10 products were not controlled substances and directed the return of those products. But authorities held onto more than 6,000 packages of edibles containing those derivatives, claiming the products violated the Georgia Hemp Farming Act, which excludes food products “infused with THC,” unless they are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

On Nov. 2, the Georgia Court of Appeals disagreed and ordered the products and money returned to Elements. “Moreover, even if the edible products seized from Elements are not themselves ‘hemp products’ as defined by the Georgia Hemp Farming Act, they do not contain any controlled substances; they are alleged to contain only delta-8-THC or delta-10-THC, which the state concedes are not controlled substances. And if the products contain no controlled substances, then there is no statutory basis for treating them as controlled substances,” the state appeals court panel wrote.

Markels said this is one of the arguments for their appeal. Under Virginia’s law, products exceeding a certain amount of “total THC” are banned. They don’t even need to have delta-9 in them.

“In sum, a plethora of hemp products that are legal under the Farm Act are now illegal in Virginia under SB 903, which negatively impacts the interstate commerce of hemp as protected under the Farm Act,” says the plaintiff’s complaint.

Brinkema didn’t mention the Ninth Circuit ruling when deciding against the preliminary injunction. On the contrary, she wrote, “On this record, defendants have demonstrated that delta-8 THC is a credible threat to the Virginia population, and there is a strong public interest in protecting the citizens of the Commonwealth from substances like delta-8, including a vulnerable population, such as children, from hospitalizations and poisonings.”

Markels said there “certainly seems” to be the potential of this case going to the Supreme Court.

“One point of the Supreme Court is to resolve a circuit split.” He explained that there isn’t really a split between the Ninth Circuit and the Seventh Circuit because the cases were slightly different. “If the Fourth [Circuit] adopts the Seventh [Circuit ruling], then we’ll have a circuit split.”

Justin Swanson, a partner and chair of the cannabis practice at Bose McKinney & Evans, represented the plaintiffs in both the Seventh Circuit case and the Arkansas case filed by Bio Gen LLC now heading to the Eighth Circuit. He agreed that, “We are headed toward maybe a circuit split on this issue.”

In April, Arkansas enacted a complete ban on the “growth, processing, sale, transfer, or possession of industrial hemp that contains certain Delta THC substances,” including delta-8, delta-9 and delta-10.

These THC substances are “likely legal,” Judge Wilson said in his ruling.

“Under the 2018 Farm Bill’s standard, the only way to distinguish controlled marijuana from hemp is the delta-9 THC concentration level. Additionally, the definition extends beyond just the plant to “all derivatives, extracts, [and] cannabinoids.”

Swanson said that out of more than 120 known cannabinoids in hemp, the only thing that matters is that the product starts below 0.3% of delta-9 THC. “That is a hemp product, period.”

And even as the DEA has said recently that “synthetic” THC may still be a controlled substance, Swanson said they are “dead wrong” on that point.

He said the Farm Act is very clear, “They have no jurisdiction over any of these products whatsoever.”

Meanwhile, Wholesale Inc. v Holcomb, which the Seventh Circuit remanded to the lower court, has been withdrawn without prejudice, Swanson said. He said the plaintiffs wanted to wait to see if Indiana would enforce its ban on smokable hemp, “and they haven’t yet.”

A longer wait for a solution

This conundrum, along with the regulation of the non-intoxifying CBD component of hemp, has led many businesses, industry groups and state regulators to push for changes in the upcoming renewal of the Farm Act to clarify the hemp law. However, that’s not likely to happen soon. A one-year extension of the Farm Bill was included in the budget compromise approved by the House of Representatives this month.

Swanson said he supports state and federal regulations on hemp products to improve public safety, such as testing and labeling. “But you can’t pass regulations that are thinly veiled as prohibition.”