As court cases challenging a state’s authority to regulate or ban hemp-derived cannabinoids (HDCs) wend their way through courts, states aren’t sitting idly by. No fewer than 10 states have introduced bills so far this year to restrict intoxicating hemp product sales.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Court of Appeals in the Fourth Circuit and Eighth Circuit are receiving briefs from interested parties, including hemp industry groups with opposing views on how the 2018 Farm Act, which legalized industrial hemp, impacts state jurisdiction. An injunction stopping Maryland’s requirement for businesses selling hemp-derived delta-8 THC to be licensed is also on appeal.

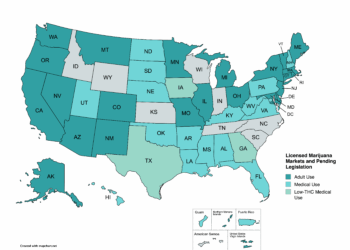

Citing public safety concerns, the number of states that seek to limit sales of products that contain intoxicating THC derivatives, and in some cases even therapeutic CBD, has grown. Last year, at least 13 states passed new HDC laws. This year, California, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, South Dakota, Utah and West Virginia have introduced similar bills.

And in New Hampshire, an adult-use legalization bill would allow the cannabis commission to regulate HDCs after the state passed a ban on HDC products containing more than 0.3% of any type of THC last year. Conversely, a Senate bill would lower the THC threshold to 0.03.

Circuit courts gather opinions

Presently, dueling views on whether states can further regulate HDCs beyond the Farm Act are being considered in appellate courts.

At issue is whether the Farm Act’s definition of industrial hemp — “any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis” — includes products that contain derivatives such as delta-8 THC, delta-10 THC and others, as well as products that contain more than 0.3% delta-9 THC in a serving, such as edibles.

The Farm Act invokes the dormant commerce clause to preempt states laws that would prohibit interstate transportation of industrial hemp. But it also says, “Nothing in this subsection preempts or limits any law of a State or Indian tribe that — (i) regulates the production of hemp; and (ii) is more stringent than this sub-chapter.”

Under the law, states can file hemp production plans with the USDA. They can also ban hemp production entirely. If they don’t do either, hemp producers are regulated by the feds.

Legal arguments have been coming down to the specific definitions of “production” and “synthetic” cannabinoids.

In Virginia, U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema ruled in October that the state, which has a USDA-approved hemp plan, does have the right to limit “total THC” in products and denied a preliminary injunction to stop the state from enforcing its law enacted last year. In Arkansas, U.S. District Court Judge Billy Roy Wilson held the opposite view when granting a preliminary injunction in September on the state’s ban of “synthetic” hemp-derived THC substances, also signed last year.

The Virginia ruling is being appealed by the plaintiff, Northern Virginia Hemp and Agriculture, in the Fourth Circuit. The state of Arkansas appealed the injunction to the Eighth Circuit. In both cases, hemp industry groups are coming to opposite opinions on the extent of the Farm Act as well.

The American Trade Association for Cannabis and Hemp (ATACH) has written “friend of the court” briefs in both cases. The trade group, which represents both cannabis and hemp businesses, sides on the need for more state regulation of what it has coined “hemp-synthesized intoxicants” (HSIs). For licensed businesses in medical and adult-use legal cannabis states, the unregulated sales of HDCs have been a scourge to the market.

“ATACH firmly believes that arguments against the ability of states to have regulatory authority over intoxicating products anywhere do so at the expense of cannabis and hemp industry regulation everywhere,” the group said in its Feb. 2 amicus curiae brief in support of the state of Virginia. “The ability of states to establish regulatory frameworks for cannabis and hemp is a foundational principle of legalization, and this fundamental state right must be protected as a matter of law.”

In its briefs in both courts, the ATACH says “Congress did not intend to legalize intoxicating substances for consumption in the 2018 Farm Bill” and that HSIs are not derivatives under the meaning of the Farm Bill.

“They are controlled substances that are often more potent than marijuana, with chemical structures and psychoactive effects that differ from non-intoxicating hemp and its organic compounds,” it said.

Even if HSIs are derivatives under the law, the Farm Act expressly allows states to regulate production and sale within their borders, ATACH says.

“This express statutory protection for state regulation operates as an important safety valve on the federal legalization of hemp, protecting the ability of states to establish state-level regulatory frameworks for hemp, on the one hand, and for adult-use and/or medical marijuana, on the other,” it said in the Virginia brief.

However, in Arkansas, Judge Wilson said “the 2018 Farm Bill’s definition of hemp does not limit its application to [the] method ‘derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids’ are produced,” as he issued an injunction on the state law, Act 629.

The Hemp Industries Association, which has advocated for hemp farmers and small business owners since 1994, agreed with the judge in its Feb. 6 friend of the court brief in the Eighth Circuit Court.

“When Congress deliberately expanded the definition of hemp, a plain reading makes it clear to the hemp industry that the sole legal metric distinguishing hemp, an agricultural commodity, and marijuana, a Schedule 1 Controlled Substance, is the concentration of delta-9 THC on a dry weight basis of the plant or product,” the group said in its brief. “The concentrations of other hemp-derived cannabinoids or isomers in harvested hemp and hemp products are irrelevant with respect to its legal status.”

The Hemp Industries Association also contends that HDCs are not “synthetic” drugs. It cited an Interim Final Rule by the Drug Enforcement Agency in August 2020, as well as a Dec. 12, 2023, notice to temporarily schedule six synthetic cannabinoids.

“None of the six compounds listed are hemp-derived cannabinoids,” it said.

Hemp companies seek to halt Maryland licensing

The question of whether states can even require hemp-related businesses to be licensed could send Maryland’s entire marijuana-licensing process in disarray if the Maryland Hemp Coalition gets its way.

The organization of hemp farmers and sellers seeks to halt the state’s social equity licensing process while the state courts hear arguments on whether the 2023 law that requires hemp businesses to be licensed is legal. They currently have won an injunction preventing hemp businesses from shutting their doors. But the state has appealed that ruling, and now the Maryland Hemp Coalition is seeking to enjoin the state from continuing with the licensing lottery, which is already delayed and under legal attack by another party over residency requirements.

“The State appears to be accepting applications and application fees from social equity applicants without warning them that the matter is presently under judicial review and that the present licensing scheme may not be lawful,” the coalition said in its Dec. 8 motion in Maryland Appellate Court.

The hemp coalition claims that because Maryland has a restrictive process to issue cannabis licenses, it creates a monopoly under state law.

“The Plaintiff retailers are willing to be licensed as recreational cannabis dispensaries if only for the purposes of continuing to sell their hemp products lawfully, but the new Act makes no provision for them to receive any licenses on an expedited or priority basis, nor does it give them any grace period within which to even attempt to get a license. Instead, it shuts them down without recourse other than through the courts,” they said in the motion.

“Plaintiffs inconsistently allege that the General Assembly created a monopoly in the cannabis market and then admit that 300 businesses have the opportunity to compete in this market,” state attorneys said in its motion in opposition to the injunction. “Given the public interest in protecting the public health through such regulation, the government has valid justification in setting reasonable limits on the number of available cannabis licenses or a lottery system for issuing such licenses without violating the Maryland Constitution.”

However, Circuit Court Judge Brett R. Wilson agreed with the hemp businesses and issued an injunction. In it, he noted that the Farm Act may preempt the state’s law to license hemp businesses. Maryland does not have a USDA-approved hemp production plan.

“Although Plaintiffs chose to not raise the issue of federal preemption, the Court finds that the CRA licensing scheme, as it applies to hemp producers, is preempted by the 2018 Farm Bill and attendant federal regulations,” Wilson said in his October order. He added, “Moving forward to the first round of new licenses provides no relief to the aggrieved Plaintiffs.”

Baltimore attorney Nevin Young, who represents the hemp coalition, said, “We don’t question the right to register per se, but we believe that if you are going to regulate, you need to treat everyone equally.”

The state has until March 6 to file their brief in the appellate court. Meanwhile, a motion hearing is scheduled for March 20 in the main case in circuit court, and a trial is set for February 2025. A spokeswoman for the Maryland Attorney General’s office declined to comment beyond court filings.

Hemp turf war

Cannabis attorney Rod Kight, who champions broader access to hemp products, said the legal arguments represent a “turf war” as cannabis becomes more normalized and large marijuana companies move into the HDC space, particularly in states where marijuana is not legal.

Kight described the dilemma as a family dispute. “But this family must address this dispute. It can’t sweep it under the carpet,” he said.

“The FDA has been singularly unhelpful” in regulating the safety of hemp products, therefore states have a lot of latitude in how they regulate HDCs, Kight added. However, “They can’t redefine hemp.”

They can even say no to hemp production. “But if they say no, they’ll be left behind economically in seconds flat.”

Young agreed, noting he could be in five different states within an hour-and-a-half from Maryland. “My general thought is the more the states try to monopolize and regulate, the more trouble they will have,” Young said. “Fundamentally, it’s about politicians who don’t understand economics trying to create a regulatory regime.”

Kight also said ATACH has no evidence that Congress had no intention of legalizing intoxicating products. He said, “Plenty of cannabis-friendly lawmakers on the Hill saw the implications. They quietly voted for it.”