Applicants for 22 medical cannabis operator licenses in Florida have been waiting more than a year for the state to award them, but the state won’t say when that might happen.

Florida is still scoring the applications for 22 licenses from among 70 current applicants who have been waiting since late April 2023, all while maintaining access to facilities they hope will one day house their medical cannabis business. At this point, that means almost a year and a half of either property ownership or rent.

A Florida Department of Health spokesperson said department concern over the potential for lawsuits has delayed licensing.

“We’re still working through the process, but we don’t have a specified estimated time frame for those awards being given out at this time,” he said.

“I understand bandwidth at an administrative agency, but it’s been a year and a half,” said Edgar Asebey, an applicant and managing partner at Asebey Life Science Law. “All the other applicants that I’m in contact with are very frustrated, and I don’t think this can go on endlessly with zero guidance.”

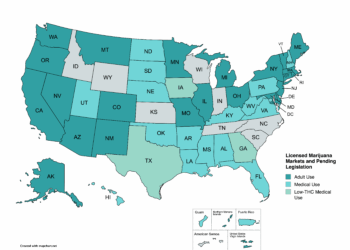

Florida currently has 24 licensed vertically integrated medical cannabis companies, with at least one more on the way as part of a program to provide black farmers with access to the market. State law requires new licenses based on the demand from medical patients, which is currently over 800,000 registrants.

At the same time, the state is preparing for the possibility of legal adult use after this November’s election. Florida voters will vote on Amendment 3, which would legalize adult-use possession. If passed, existing medical operators would be able to sell to non-patients, but the legislature would have to act in order to create more licenses.

The state Department of Health published an emergency rule on Feb. 3, 2023, creating an application window in April of that year, during which applicants would compete for 22 available operator licenses. Florida licenses medical cannabis operators as vertically integrated medical marijuana treatment centers, and license holders are permitted to open as many dispensaries as they would like.

This is how Trulieve, which is largely financing the campaign for Amendment 3, is able to operate over 150 dispensaries throughout the state.

Florida had 859,026 registered patients by the end of FY 2023, according to an annual state report on medical marijuana trends.

State law requires that four new medical cannabis licenses be made available, in addition to the original 24, for every 100,000 patients that enroll. This means that technically, the state should have 32 additional licenses available beyond the original 24. The state has six months to issue those licenses every time the patient count hits another 100,000 threshold, but Florida’s medical cannabis law does not set any consequences for missing that deadline.

“The effort to issue new licenses was an attempt to catch up to that standard,” said Jeff Sharkey, president of the Medical Marijuana Business Association of Florida.

Fear of litigation slows review process

Sharkey said he had heard from applicants who reported that the state reached out to them to clarify information in their applications. He suggested that this shows the state is still at work reviewing submissions.

“They’re just trying to limit litigation challenges,” said Sharkey. “The idea is to be as defensible as possible. They can get into a briar patch with extensive litigation.”

The concern for legal action is not unfounded. New York’s adult-use rollout was delayed after lawsuits challenged the Empire State for reserving the first round of dispensary licenses to individuals with prior cannabis convictions from within the state. Meanwhile, Alabama is still attempting to launch its medical cannabis program after lawsuits blocked three separate rounds of license awards.

Last December, OMMU Director Christopher Kimball, presented an update on the licensing process to the state House of Representatives’ Healthcare Regulation Committee. He said he hoped the state would be able to issue the 22 new licenses by April 2024. He noted that the concern for litigation could slow down the review process.

“If I rush them and we get a bad result, we get sued and lose and nobody gets their licenses,” said Kimball.

Since then, OMMU has released no further public comments about the licenses.

“We heard back [shortly after submitting] if there were any deficiencies and we got a chance to correct those. Since then there’s been zero feedback, and it’s been a year and a half,” said Asebey. “That is just untenable.”

Because the emergency regulation did not include a set time limit for the licenses to be issued, applicants have little to no legal standing to sue until the 22 finalists are announced, according to Asebey. He noted that it would not surprise him to see lawsuits at that point.

Licensing lawsuits already pending

The state is currently in the middle of several lawsuits filed by failed applicants for so-called Pigford licenses.

Pigford licenses are reserved for black farmers. The name “Pigford” refers to a decades-old federal lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Agriculture that sought redress for black farmers who were chronically denied benefits, such as disaster aid or loans, at a disproportionate rate compared to white farmers.

The state accepted 12 applications between March 21 and March 25, 2022, of which one was approved for licensure. Subsequently, the 11 remaining applicants sued, resulting in the legislature making all 12 licenses available, assuming that the applicants meet a minimum threshold in terms of their application score.

The state legislature passed an omnibus healthcare bill, SB 1582, in June that included some changes for medical marijuana license applications, including allowing applicants up to 90 additional days to cure any deficiencies in their application, while also removing the death of an applicant as a pretense for denial.

Those changes could render three Pigford appellate court cases moot, including two in which the plaintiffs say they were not given enough time to correct their applications, and a third from the estate of a man who applied and then passed away.