Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, where cannabis is still illegal, had a question for Attorney General Pam Bondi about how the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians were getting their cannabis to state residents.

“Can I get your commitment from DOJ, not you personally, but can I just get a definitive answer that there’s no ‘there’ there? That they are legally transporting it, or that we do have something here that doesn’t comport with federal law?” he asked approximately four hours and 20 minutes into a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on Oct. 7.

“I will absolutely have my team look at that issue,” Bondi responded, saying she was not familiar with “that establishment” or the tribal dispensary’s app.

Under federal law, distribution of a Schedule I controlled substance is illegal, and the Federal Drug Administration must approve any controlled substance for interstate commerce. So Bondi said transporting cannabis from reservations to state territory would be illegal.

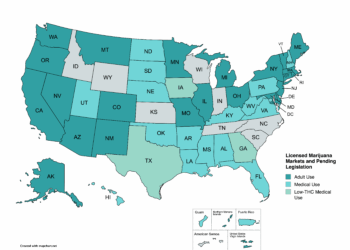

But that hasn’t stopped legalized states such as Minnesota, Michigan and Washington from signing compacts that allow tribal cannabis to be sold outside Native American territories.

Minnesota signs seventh cannabis compact

On Dec. 30, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and the Office of Cannabis Management (OCM) announced its seventh tribal compact authorizing adult-use cannabis commerce and said more are to come as the state is still in the early stages of launching its adult-use market.

This latest agreement is with the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa.

“The cannabis compact between Bois Forte and the state of Minnesota presents a significant opportunity for economic growth, job creation, and community development, shaping a better and brighter future for Bois Forte,” said Shane Drift, District I representative for the Bois Forte Band, in a statement.

Two weeks earlier, the OCM announced an agreement with the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, which opened the first dispensary in the state after adult use was legalized in 2023.

“This partnership opens a new outlet for state-licensed cannabis businesses to access and sell legal cannabis and honors the independence of the members of the Red Lake Band,” said OCM Executive Director Eric Taubel in a Dec. 15 statement. “We look forward to their cooperation in bringing more cannabis supply to the state and seeing their cannabis operations develop and thrive while respecting the Red Lake Band’s autonomy.”

In Michigan, the Cannabis Regulatory Agency (CRA) announced Dec. 18 that it signed a tribal cannabis compact with the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians. The Pokagon Band launched its Rolling Embers retail store and consumption lounge in 2023.

The compact was actually signed Oct. 20, along with another compact with the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, according to CRA spokesman David Harns. Michigan signed a compact with the Bay Mills Indian Community on July 24.

“We are pleased to finalize this compact with the Pokagon Band, which reflects our shared commitment to a safe, equitable, and well-regulated cannabis marketplace in Michigan,” said CRA Executive Director Brian Hanna. “This agreement provides regulatory clarity, supports responsible commerce, and advances our mutual goal of protecting public health and safety.”

Tribal cannabis compacts outline compliance rules

Mary Jane Oatman, executive director of the Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association, said Bondi’s comments were like a canary in a coal mine.

“It caught the attention of every tribe in the country,” she said.

Oatman called the history of tribal cannabis sort of a “reverse Lewis & Clark expedition,” where a lot of the cannabis plant knowledge and intellectual property came from the West to the East.

She said from the early onset of legalization, tribes that signed compacts with states have seen “harmony between state and tribal programs,” such as in Washington.

Washington currently has 23 compacts with tribes, according to a spokesperson for the Liquor Cannabis Board (LCB).

“When it comes to protecting public safety and health, for everything, the compact is the way to go,” Oatman said.

Michigan’s compact with the Pokagon Band allows it to purchase cannabis from and sell to state licensees, transport cannabis outside tribal land to state licensees, integrate Metrc track and trace, and collaborate with the CRA on inspections and enforcement.

Tribal Council Chairman Matthew Wesaw said, “We are pleased to have agreed on a framework that respects tribal jurisdiction, while accounting for legitimate state interests, to further advance our common goal of expanding commerce in Michigan’s cannabis industry.”

Minnesota has also signed compacts with the White Earth Nation, the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, the Prairie Island Indian Community, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

While each agreement is unique to the tribe, they all contain requirements for product testing, data gathering and analysis, track and trace, and package labeling.

OCM Director of Communications Josh Collins said all of them are able to open up to eight dispensaries and one manufacturing site off of tribal lands, but no more than one location in a city and three in an individual county.

“We’re looking at it in a unique way to recognize their sovereignty,” said Collins. “We’re eager for more relationships between tribes and state licensed businesses.”

Darrell G. Seki, Sr., chairman of the Red Lake Nation in Minnesota, said the tribe has been perfecting unique strains of cannabis in their growing facilities over the last five years.

“Our goal from the beginning has been to produce the highest quality cannabis products that are free of all toxins and impurities. Consistent testing has verified that we have reached our goal,” he said. “Now that our cooperative agreement with the state has been finalized, we are looking forward to sharing our top shelf products with the Minnesota market.”

The Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa signed its compact in October. Tribal Chairman Bruce Savage said in a statement, “This compact reflects the respect and responsibility that define government-to-government relationships. Our Fond du Lac Band has invested significant time and effort to help shape a fair and equitable agreement that upholds our values and affirms our commitment to responsible cannabis regulation in Minnesota.”

In contrast, California doesn’t have a compact program, and tribal businesses have had to buy into the state’s licensing program. The result has been a sometimes acrimonious relationship where tribal governments feel their sovereignty is not being respected.

For example, members of the Round Valley Indian Tribe in Covelo, Calif., are suing the California Highway Patrol and the counties of Mendocino and Humboldt alleging warrantless searches and seizures and destruction of property in July 2024 based on the absence of a state or county cannabis license.

While there was a search warrant supported by a Humboldt County deputy, the CHP weren’t named on the warrant. The tribe and its members also claim in a Sept. 23, 2025, court filing that under case law, “such civil/regulatory laws are unenforceable against Indians in Indian country.”

Wilkinson Memo says Cole Memo priorities apply

Following the Department of Justice’s Cole Memorandum in August 2013, which outlined eight law enforcement priorities for cannabis in legalized states, the U.S. Attorney General’s Native American Issues Subcommittee reviewed how the directive would impact “Indian Country.”

In an Oct. 28, 2014, memo, DOJ Director Monty Wilkinson said the eight Cole Memo priorities would guide U.S. attorneys, and they should consult with affected tribes on a government-to-government basis.

“Indian Country includes numerous reservations and tribal lands with diverse sovereign

governments, many of which traverse state borders and federal districts. Given this, the United

States Attorneys recognize that effective federal law enforcement in Indian Country, including

marijuana enforcement, requires consultation with our tribal partners in the districts and

flexibility to confront the particular, yet sometimes divergent, public safety issues that can exist

on any single reservation,” Wilkinson’s memo said.

“Nothing in the Cole Memorandum alters the authority or jurisdiction of the United States

to enforce federal law in Indian Country. Each United States Attorney must assess all of the

threats present in his or her district, including those in Indian Country, and focus enforcement

efforts based on that district-specific assessment.”

Following Tillis’ and Bondi’s remarks at the Senate committee hearing, Principal Chief Michell Hicks of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians issued a statement saying Tillis mischaracterized the tribe’s cannabis activities.

“Senator Thom Tillis knows full well that the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians operates squarely within the law. Yet once again, he has chosen to ignore that truth to advance his own political agenda,” he said Oct. 9.

“Our operations are fully compliant with federal and tribal law, guided by safety, transparency, and accountability. Senator Tillis’ attacks are not about legality; they are about ego. To suggest the EBCI would endanger children through marketing or sales practices is inaccurate and it is offensive to the values that guide our tribe.”

Meanwhile, regulators in legalized states are watching out for federal action, but they aren’t altering their practices.

“We are certainly paying attention to it. But it’s not something that’s changing our compacts with tribes,” said Collins in Minnesota.

Washington State LCB spokesperson Sam Guter said, “We don’t have any concerns regarding the federal comments. There is a lot that has to happen, and we are watching for any changes or updates.”

Harns for the Michigan CRA declined to comment.

Department of Justice representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Oates said the ICIA is continuing to advocate for the best practices seen in states with legal cannabis. She said she applauds Hicks and the Eastern Band of Cherokee for protecting their tribal sovereignty while building local relationships.

“We might hear a lot of noise from federal elected officials,” she said. “But when the rubber meets the road, the Eastern Tribe has done right at the local level.”